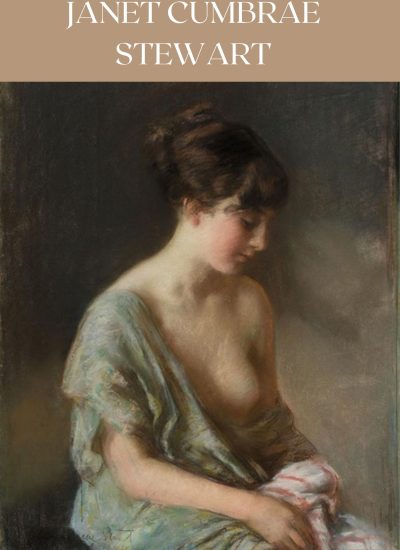

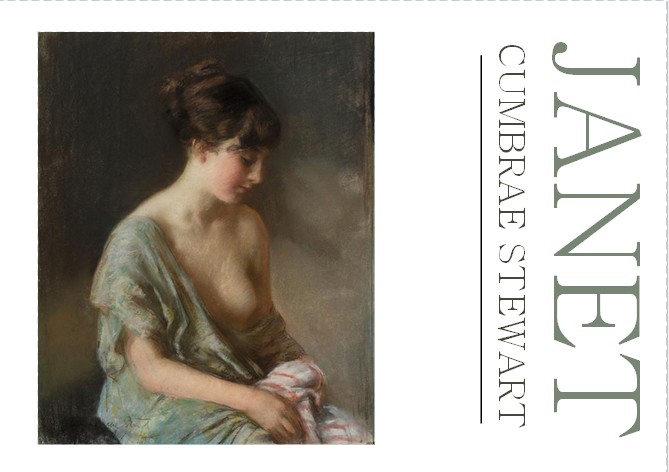

Janet Cumbrae Stewart

Research toward catalogue raisonne – free download below

Cumbrae Stewart (1883-1960) was born Janet Agnes Stewart on the 23rd December 1883 at Montrose in Brighton, Victoria. She was the youngest of ten living children born to Francis Edward Stewart (1833 – 1904) and Agnes Catherine Park (1843-1927). Francis Stewart was born in England and met Agnes Park in New Zealand where they married in 1863. The family moved to Victoria between 1871 and 1873 where Francis worked as a chief inspector for the National Bank before going on to become a managing director first for a wool broking firm, and later for a stock agent.1 He purchased Montrose in 1881, where his family lived a very traditional upper – class existence, with a slew of staff to help run the household and property. The family also owned other holdings including a country retreat at Officer, known to the family as The Wilderness.2

By the time Janet was born, her older siblings were already young adults. The eldest, Francis (b. 1865) was away studying law at Oxford and one sibling, Walter (b. 1875), had tragically died on Christmas Day in 1876, having choked on three-penny bit. Janet was one of only three girls, Mary (May) was the eldest, born 1871, Beatrice (Bea) born in 1879 and Janet (Jan) the youngest, was born four years later. As was the norm, they were raised with all the limitations of well brought up young ladies of the era. In her own writing, Janet laments not being born a boy so she could follow her brothers into private school.3 The three younger siblings, Beatrice, Reginald (Rex, b. 1881), and Janet were very close and shared many happy memories, especially of their time spent at The Wilderness. Here they were able to ride, and roam freely about the property. But things were not always easy. In Janet’s own recollections, she describes her father as “a good Victorian man whose word was law” and disobedience punished with a whip, and of her beloved mother who never interfered as she was raised to believe that a husband was always right. Her brother Francis seems to have adopted his father’s approach to managing the behaviour of his younger siblings. A couple of them recall his tyrannical treatment of them during their parent’s absence in England in 1891: a time in which Janet her-self describes as being ‘dark days’.4. Francis Sutton Cumbrae-Stewart was described by historian, Helen Gregory, as rigid and authoritarian, “whose commanding physical presence was daunting.” 5.

Agnes Stewart was reluctant to leave her small children and shed tears at their departure, though she had the presence of mind to install their old family nurse, Emmie (Margaret Lynch) in the house to offer comfort in her absence. Emmie had been like a mother to the young Janet, and it was with her that she shared all her hopes and dreams. Janet later wrote “her death half crushed me and if ever there was a saint, she was one.”6.

The family fortune took a substantial hit as a result of the 1890s depression, and although she stayed on to help the family through that difficult decade, Emmie was eventually let go. Their governess, Miss Marion Lawes, didn’t last as long. She was let go in 1892 when Rex was sent to school shortly after the family returned from England. Janet recalls her arriving each morning from Caulfield to give the three younger siblings their lessons.7 She was only 19 years old and very poor. Despite this, she was good to her young charges, bringing them gifts. Janet was given a book, Flisk and his Flock, which she so treasured that it was still in her possession after she returned from Europe.

After Miss Lawes, Beatrice and Janet joined the Games children at the Manor House under the instruction of their governess, Miss Archer. Norah and Winnie Gurdon also attended those lessons.8 Like Janet, Norah also went on to become a professional artist and the girls remained life-long friends. The arrangement with the Games family, however, was short-lived. After only 3 terms, they were taken away and the responsibility for their education fell to their older sister, May. Beatrice however, found the situation so distasteful that she rebelled and was sent off for lessons with a Miss Jones at Ronbaix (a house next door to Middle Brighton station), leaving her young sister alone in the unhappy situation with May.

During their early years, Janet and Beatrice also received instruction in several suitable ‘past times’, that were considered desirable in an accomplished young lady of the day. These lessons included dance, piano and drawing, the latter of which Janet was to particularly excel.9 Lessons in drawing were taken at Mrs R. Sadlier Foster’s Ladies School under the instruction of Zena Beatrice Selwyn Hammond, who later married Janet’s eldest brother Francis in 1906.4. Zena would join numerous charitable societies in Queensland from which she delivered lectures to modern young women on the morality of their dress and reading habits.10.

Even as a young woman, Cumbrae Stewart took her art seriously, though found it difficult to work without interruption at home. To remedy this, she transformed the coach-house into a cosy studio, though to her dismay, her brothers insisted on sharing it.11 In her late teens, she became a student of landscape painter, John Mather, and joined his group on outdoor sketching expeditions.12 Janet would become life-long friends with another of Mather’s students, Jessie C. A. Traill, who she likely already knew through the family’s attendance at St. Andrew’s Church in Brighton. The pair would continue to advance their artistic skill at the National Gallery School a few years later.

Although the family managed to weather the financial storm of the 1890s, their situation slowly worsened following the sudden death of the patriarch in 1904. Having descended from a prominent heritage, the Stewart family had always enjoyed an elevated status in society and this was a particular point of pride to their eldest sibling, Francis, who became convinced of a link between his family and the Stuarts of Bute while studying at Oxford, though he was never able to prove it, and had there been one, it was likely illegitimate. He supposedly once remarked that “if not for a little ‘misfortune’ his line of Stewarts would have occupied the English Throne.”13 To distinguish his family as separate from other Stewart’s in the world, he decided they should all adopt Cumbrae as a hyphen to their sur-name and so it was changed by deed poll.14 This additional name would serve a greater purpose for Janet who later identified herself simply as Cumbrae Stewart and so avoided, to a certain degree, the limitations and scrutiny attached to her sex.

In the last few decades of the 19th Century, women from the upper class who had demonstrated an aptitude for painting, could see an escape from the historic restrictions and societal expectations through art. Since the very early days of white settlement in Australia, growing numbers of women had forged their own lives through art. Although there was still a prevailing belief that girls need not be given an extensive education to fulfill their role as a wife and mother, the daughters of the upper-classes did receive a good education in drawing and painting. So, it is not surprising then that many young women who excelled in this field, turned their talent into a profession, especially as there were not many other suitable employment options open to their class before the war. Although a wife becoming a professional artist in those days, still reflected badly on her husband’s ability to provide for his family, a single woman need make no such concession.

Amidst her father’s expressed disappointment, Cumbrae Stewart entered the National Gallery Art School in 1901, where she joined a close-knit circle of friends including Norah Gurdon, Jessie Traill, Dora Wilson and Susie Gregory.15 Female students far outnumbered their male counterparts in enrolments at the school, though many were not simply studying as an ‘accomplishment’. Several who were enrolled during this time, went on to become professional artists, and Janet was certainly one of them. During her years at the school, she won several awards: 1903: Drawing a Head from Life – 3rd Prize. 1904: Drawing from Antique (Painting Students) – 1st Prize. 1905: Painting still life – 1st Prize. 1906: Portrait Study – 2nd Prize, Painting, Head No.1 – 1st Prize, Drawing figure from life – 1st Prize, Drawing Antique figure (Painting students)- 1st Prize. She also won third place in the coveted Travelling Scholarship in 1908 for The Old Gown (Figure 1). First and second place were both awarded to Constance Jenkins. 17

Cumbrae Stewart benefited from the support and encouragement given by her painting teacher, L. Bernard Hall, who later expressed misgivings that she had missed out on the Travelling Scholarship during her years at the school.18 Hall would also later become a patron, purchasing a landscape from her first solo exhibition in 1911.19 That he had a great influence upon her work is evident in her preoccupation with the nude as a subject, but also in her fine rendering of the human form, particularly skin tones, for which she was greatly admired. Janet also studied drawing at the National Gallery, under the tutelage of Frederick McCubbin. 20

The years following her formal art education afforded the young artist an even greater level of independence. She commenced exhibiting widely, in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales, later under the management of Mr Gayfield Shaw, who was an artist and gallery owner in Sydney.21 Shaw acted on behalf of Cumbrae Stewart between 1918 and 1922, booking commissions, organising exhibitions and the transportation of artwork, as well as processing sales and overseeing the production of catalogues. Although she held her own solo exhibitions, she also participated in several group exhibitions, such as the Victorian Artists Society. She also joined groups of friends on painting trips.

In 1916, Cumbrae Stewart and friends Jessie Trail, Norah Gurdon, Vida Lahey, and Susie Gregory travelled to Tasmania where they painted scenes around Hobart. In 1818 a group of them went on a 10 day camping trip, and in 1919 she and several others went to Apollo Bay. On this particular trip, she brought her own model along and painted several ‘charming pastels of girls amongst rocks & sand”.22 She also rented several studio spaces in those early years.

Exhibition catalogues, letters and newspaper articles identify at least four: Stallbridge Chambers in Little Collins Street, Temple Court in Collins Street, Peterson’s Building in Flinders Street and Grosvenor Chambers at 9 Collins Street. In the Australian Art Association 1920 exhibitions catalogue, Cumbrae Stewart lists her address as being 612 Collins Street which might be the space she talks about seeing a mental vision of. She told The Age that she was desperately seeking a new space following the developer’s decision to demolish Temple Court and was travelling by tram when she received a mental vision of the perfect studio in Collins Street. So strong was the vision that she immediately headed there and was rewarded for her decision. 23 Years later she discovered that her father had also once occupied the same space as an office. It was during this time, in 1918, that Cumbrae Stewart also secured a parcel of bushland in Hurstbridge, fondly named “Wanna”, upon which her brother Ted helped erect a studio.24 The property remained in her possession until she sold it in April of 1960.25 She used to work regularly in her studio there, but this ceased following the Black Friday Bushfires in 1939.26 Over the years, several members of her family also made use of the property, on weekends and holidays.

Despite her new-found independence, Cumbrae Stewart continued to call Montrose home, but in 1917, the high cost of maintaining the property and became too much and the land surrounding the beloved family home was subdivided into 10 separate blocks and sold at auction on Saturday 3rd March 1917. 12 months later, the house itself sustained extensive damage when a ferocious storm hit Brighton on the afternoon of Saturday 2nd February.27 Cumbrae Stewart’s 10 year old niece, Marwin, recalled the chaos. She wrote that they were all having afternoon tea in the dining room when the storm hit. She was watching from the window as the wind brought down a big Cyprus tree, and tore large limbs from others, flinging them about the property. It also shattered windows in the house, though fortunately the room they were in remained intact. The storm had passed after only a few minutes and the youngster had felt no real fear, but her Aunt was not so lucky. During the height of the storm, the lock on the upstairs room Cum-brae Stewart was in jammed and she found herself stuck. When she was helped out in the wake of the storm, she came downstairs in a wild frenzy “wringing her hands and calling out at the top of her voice “Oh, we’ll all be Killed! We’ll all be killed!”28 Fortunately, nobody was hurt during the incident, though the house itself was so badly damaged that it was initially believed that it would need to be demolished. Thankfully, it did not come to that, though the house too, was eventually sold toward the end of 1922.29 With her aging mother displaced from her home, there must have been some expectation of her as a daughter, to support her sisters in caring for the family matriarch. Never being one to conform to familial expectations, she dodged that bullet as skillfully as she had any of the other conventions that might have befallen her as a woman of that era. Instead, she left Australia for England to further her career In the company of her married sister, Beatrice (BEB Peverill). Travelling on board the Aeneas, the pair arrived in Liverpool on the 21st July 1922 for what was to be a limited stay.30 In an interview with the Argus upon her return to Australia, Beatrice indicated that since leaving England, her sister had been very lonely and was not expected to remain long, indeed Cumbrae Stewart had already secured a return passage, but fate had other plans. Cumbrae Stewart had arranged to hold an exhibition of her work shortly after their arrival, though to her horror, most of the pieces she had selected for inclusion had some-how been damaged beyond repair during the journey and had to urgently be replaced. And so followed the frenzied task of securing a suitable studio in which to create her new collection.

Cumbrae Stewart had had the sense of mind to accepted commissions during the journey, which she no doubt later used to pay the rent on the studio. The captain had generously provided her a small studio space below the bridge from which to work. An exhibition of her portraits and travel sketches was held in the music room shortly before the ship arrived at its destination.31.

Beatrice revealed in the interview that upon arrival she and her sister traipsed tirelessly around London, going from agent to agent, on a mission to quickly secure a suitable studio. At the end of an exhausting first couple of weeks, Cumbrae Stewart took temporary possession of a big studio once belonging to Charles Stabb, but it was ultimately deemed unsatisfactory as it didn’t contain a ‘living room,’ and so the hunt was not over. Cumbrae Stewart, who longed for a space in Chelsea alongside her fellow artists, had to settle for a studio flat in West Cromwell Road, as Chelsea was beyond her financial means. 32

When Beatrice left her sister, she took with her Power of Attorney to act on her behalf on financial matters back home in Australia during her absence. Beatrice managed the administrative side of Cumbrae Stewart’s exhibitions and probably the rental and management of her property at Hurstbridge. This was a decision Cumbrae Stewart would later come to regret as Beatrice turned on her after she went to England and refused to hand it back.33

Although Beatrice had returned to Australia, Cumbrae Stewart was not alone in London. She was related by marriage to the Countess, Lady Darnley, who was born Florence Rose Morphy in Victoria. The Countess was reported to have attended her early exhibitions in the company of others of similarly regal sounding heritage. It has been said that she was extremely well connected and could quickly put anyone on the path to success through her association, and was particularly helpful to her fellow Australian’s – Cumbrae Stewart included.34

If Cumbrae Stewart was still entertaining plans to return home, they seemed to have been put off following her solo exhibition at Walker Galleries in February of 1923. It was deemed a great success and resulted in numerous commissions that kept her busy and her mind off thoughts of home, and by then she was starting to make a life in England. She later wrote that although she was living from one sale to another she ultimately decided to stay in England, selling her return ticket to Melbourne and living on the proceeds. 35

Sometime before July of 1924, Cumbrae Stewart secured the long-desired Chelsea studio, located at 239 Kings Road. From the beginning, she appears to have been sharing the space with Hylda Marion Atkins, an etch-er of some talent, with whom she also exhibited occasionally in Australia between 1924 and 1927.

Hylda Atkins, who often went by the name Tommy, was the sister of Donel-la Anne Atkins who, in 1916, married Dr Hugh Ferguson Watson, the man responsible for inflicting grievous injuries upon four Suffragettes at Perth Prison through a program of forced feeding.36 Watson would ‘deal’ with Suffragettes who refused to eat during their incarceration by restraining them and violently forcing a feeding tube down their throats. Arabella Scott, who later migrated to Australia, was one of his victims. She was force fed in this manner three times a day over the course of the 26 days she spent in Perth Prison. In her memoir, Scott describes a force-feeding tube being driven into her stomach as bits of her broken teeth washed around with blood in her mouth.37 Donella’s marriage wouldn’t last and she herself went on to become a doctor.

The adoption of the name “Tommy’ likely evolved as an adaptation of “Tommy Atkins” which was slang for a common soldier in the British Army – more commonly known today simply as a ‘Tommy” – a term well used during World War I.

Cumbrae Stewart continued to exhibit in England to good reviews, indeed reports suggest that Queen Mary herself attended her 1924 exhibition and complimented Cumbrae Stewart on her achievement.39 She personally selected a painting that remains within the Royal Collection today (Figure 2).

This situation changed somewhat with her 1925 exhibition at Beaux Arts which lead to some eyebrow raising over her approach to some of the nudes. Reviewers claim that some in the collection contain ‘startling gestures’ – particularly those containing “a big floppy black hat, a feathered head-dress, and a pair of chic slippers.”40 These works include Joie de Vivre, Haughty Princess and Red Slippers (to name a couple) and they certainly do stand out in stark contrast to her general work in this genre for their bold poses, which would have been quite shocking for a woman artist at the time. Cumbrae Stewart responded to her critics, explaining:

“The nude alone does not satisfy me, and I don’t think it satisfies most people. I just draw in this way because I like to – although I confess that when I first started doing it in Australia, I was a little afraid. I am not now. In Australia to-day they have a healthier attitude to the nude, I think, than even you have over here. We love the open-air life on the beaches and like to go about unashamedly with little on.” 41

One critic described the model as possessing a look of ‘indolence’ in one, and ‘insolence’ in another. The model in all instances was no other than Hylda Atkins herself, who was described by Cumbrae Stewart’s niece, during a visit with her Aunt in Italy in 1932, as being ‘very delicate and spoilt’.

Atkins stepped on to the road from behind a bus in 1945, and was struck down by a heavy vehicle. She was taken by ambulance to hospital with a fractured skull and ribs.42 Her condition at the time was described as ‘grave’ though she survived her injuries and passed away on the 21st September 1968 at the age of approximately 73 years. Her tombstone bears the name Hylda (Tommy) Atkins.

Over the coming years, Cumbrae Stewart had works accepted for exhibition at the Salon des Artistes Fracais in Paris, receiving honourable mention for Noonday Rest, 1919 (Figure 3), as well as The Royal Society of Portrait Painters, the Royal Glasgow Institute of Art, the Royal Academy in London, and the Society of Women Artists, punctuated by several solo exhibitions at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London. She also represented Australia at the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley in 1924 and the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition in Dunedin in 1926. During this time, she also exhibited regularly in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide. The subject of her painting over this period suggests Cumbrae Stewart travelled around the UK and Brittany in 1923 and across to Avignon in 1925, then on through Italy in 1926. Upon her return to Australia, she told The Bulletin that she travelled alone in Europe, avoiding the express trains whenever possible, opting in-stead for the slower goods trains so she could better enjoy the scenery.43

It is likely in Cassis, between 1925 and 27, that Cumbrae Stewart met Argemore ffarington Bellairs, (Figure 4) better known as Bill, who was making a living driving a taxi that she owned herself. She was a well-known and liked personality in the community and was very conspicuous.44 Bellairs was extraordinarily tall and heavy set, wearing tweeds and a beret, her hair cut short and slicked flat against her scalp, a cigarette dangling from her hand.

Although a British subject, Bellairs claims to have spent most of her life in France, having spent her childhood in Caen.45 She hailed from good lineage though by all accounts, her childhood was not a happy one. She was the last of 8 children and was unwanted and unloved. She moved to Caen with her mother and siblings after her father abandoned the family for another woman. Sadly, her mother died shortly afterward, leaving the young Bellairs in the charge of a sadistic brother-in-law. During the First World War, Bellairs signed up as volunteer nurse to the French Red Cross with her then lover, Maud Jennings, with whom she had been living in London.46 Both served initially together in France for some time but, when the opportunity came up to go to Salonica in Greece, both jumped at the chance. 46. It was here that they spent the remainder of the war, though their decision to go would have life-long repercussions for Bellairs, who contracted Malar-ia and suffered with its symptoms for the remainder of her life. Soon after the war, Maud married a doctor she met in Salonica while Bellairs took up nursing in Paris until she moved to Cassis in a bid to control her Malaria symptoms. 43 In Cassis, Bellairs was part of a colony of famous writers and painters, including Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Clive and Vanessa Bell, and Virginia Woolf, Cumbrae Stewart, Pascin, and Foujita, most of whom were only resident during England’s harsh winters. 47

It is through her meeting with Bellairs that I believe Cumbrae Stewart experienced a sexual awakening. She was not the first. A personal memoir belonging to a lover of Bellair’s speaks of how she had herself surprisingly and unexpectedly succumbed to Bellairs’ charms after several years of marriage:

I must try to set down a deeply moving experience in a totally new region of love, lesbianism. This shocked me, shook me to the core and cured me for all time of my cheap and ignorant criticisms of lesbianism. 48.

This theory goes a long way to explain why Cumbrae Stewart appears to have stopped painting nudes of young women all together around this time. Cumbrae Stewart continued to rent a studio in Chelsea until at least 1928. 49 She moved to Laiguiglia in Italy in around 1929, where she and Bellairs rented a house known as Casa Verria. Her decision to leave London is not known, though it was likely to do with her relationship with Bellairs and her desire for privacy. In 1932, when Cumbrae Stewart’s niece was visiting her aunt in Italy, Hylda Atkins, recently returned from a trip with Bellairs to the US and Canada, was living in a flat nearby and Mary (Cockburn) Mercer (Figure 5) was also mentioned as being in the area, in the company of her “American friend” who we know to be Alexander Robinson, the watercolourist. Bellairs is commonly believed to have been acting as Cumbrae Stewart’s manager though in the early thirties, this task seems to be in the hands of Major Fred-erick Lessor, founder and director of the Beaux Arts Gallery in London. 50

Although she continued to paint, Cumbrae Stewart’s exhibition activity began to dwindle from this point on, possibly as a result of the Depression, though she did hold an exhibition at the Casa d’artisti, an art gallery located a short distance away in Milan, (not the home of the artist), in the first part of 1932.51 One of her landscapes was purchased by the Museo del Novecento and remains in their collection today (Figure 6). The Argus also reports her having had a studio in Alassio near Florence prior to this.52

In 1934, Bellairs and Cumbrae Stewart moved on to Villeneuve outside Avignon. In an interview published in The Australian, Cumbrae Stewart speaks of an atmosphere of ill-will toward the English after the Abyssinian war and brewing tensions under Mussolini may have underpinned the decision to move.53 Here they rented a portion of the former palace of the Cardinal de Giffons for £4 per month. It sat on a hill overlooking Avignon and the Rhone, and they celebrated the move with a housewarming party in honour of the Cardinal, with guests wearing 11th Century costume, and Bellairs dressed as the Cardinal himself in a purple silk robe, skull cap, and small white moustache, fashioned from a snipping of their dog’s tail. 54

In a letter home to her brother in 1934, Cumbrae Stewart speaks of an Austrian modernist artist residing nearby who was encouraging her to adopt a more modernist approach to her work. The letter gives an insight in to her life and mind at this time:

I am painting a good deal at present. There is an Austrian artist here, very modern. I am trying to get hold of the modern ideas, as now days it is all the rage, and, as you know, it has been so for 30 years. I have done an ultra-modern picture which they love. I don’t feel in sympathy with their ideas, that is, for pictures. As decora-tions, I find them most attractive. It is the swing of the pendulum. Painting in the old style had become boring to many minds. So, they go to the other extreme and paint ugly models in a brutal way. The funny thing is that this modern artist thinks my work awfully good and says that if I only followed his ideas, I would become celebrated! I have been working in oils lately. I feel that I want a new medium to send me back to pastels with a fresh vision. Our friend, N. de Savlou is sitting for me, and I have some other portraits. My last picture in the Paris Salon was a child. I have not sent to the Royal Academy or The Salon this year, as it is a very expensive business. 55

Cumbrae Stewart’s final European exhibition fittingly took place at Walker’s Gallery in 1936, the venue for her first London solo exhibition, though celebrations were marred by Hitler’s occupation of the Rhine. Cumbrae Stewart reported that all attendees, including herself wore black in mourning for King George.56 The following year she returning to Australia for a holiday in the company of Bill Bellairs on board the Dutch ship Meliskerk from Antwerp, setting foot on Australian soil for the first time in 14 years on the 17th February 1937.57 Bellairs told Smith’s Weekly that the ship was followed for a short time by a Spanish destroyer, leaving those on board to pass a few uneasy days.58.

The travellers were met at Victoria Dock but several of Cumbrae Stewart’s artist friends along with her nieces, Dadge and Marwin. They stayed initially with her sister Beatrice in Brighton, who had since their departure, become widowed and was remarried to Harry Francis – a man Cumbrae Stewart despised for his cruelty.59 It was here that evening that the family gathered to celebrate the return of their famous sister. The next fortnight passed in a blur of parties and reunions, reacquainting old friends and fellow artists, including Norah and Winnie Gurdon, who were also close friends of the wider family.60. On the 18th May, 1937 Cumbrae Stewart opened an exhibition of her work at the Athenaeum Gallery, which consist-ed mostly of scenes of France and Italy along with a couple of her earlier nudes. With the inevitability of another war, the pair gave up any idea of returning to Europe in the immediate future and settled into a quiet life in Melbourne.

In 1939, Mary Cockburn Mercer arrived in Melbourne to shelter from the war and their acquaintance was renewed. Mercer was well-known for hosting glittering parties and Cumbrae Stewart was amongst the guests – probably in the company of Bellairs.61 Although it has been reported that Mercer had an affair with Cumbrae Stewart in Europe, I have so far discovered no evidence to support this rumour. Bellairs and Mercer probably knew each other long before either of them met Cumbrae Stewart, as both were well-known residents in Cassis. Mercer, who had been in a long-term relationship with her former art teacher, Alexander Robinson, had recently left him for a German photographer, Adolf Hans Weichmann, who she had met in Milan in 1931, and travelled with to Northern Queensland and Spain during the onset of war.62 Mercer lost touch with Weichmann soon after he had been called back to Germany and after an extended period with no word from him, she presumed him dead. 63 Cumbrae Stewart was 54 years old when she returned to Australia, and after a short stay with her sister in Brighton, lived with Bellairs, sharing their time between No. 4 Margaret Street, South Yarra and her property, ‘Wanna’, at Hurstbridge.64. After returning home, Cumbrae Stewart held only two more solo exhibitions before her death in 1960, both at Velasquez Gallery in Melbourne. The first of which was held in 1942 and the second in 1947. Reviews of the 1947 exhibition suggest that her subjects included figures, landscapes, and flower studies though those mentioned hailed from her early career. Later reports of this exhibition state that Cumbrae Stewart was firmly against any form of promotion, so it was not well attended. 65 The Brighton Southern Cross writes that Cumbrae Stewart continued working up until her death, painting portraits of well-known people including members of the Baillieu family. Marwin took her young children to the studio to sit for several portraits and her last painting is believed to have been that of her nephew, Ean, which was completed just prior to her death. In a letter to Ola Cohn, Jessie Traill breaks the news of Cumbrae Stewart’s death. She wrote that she only heard the news herself through a call from the family, as Cumbrae Stewart insisted that no notice or obituary be published and that the funeral be a private affair. Of Bellairs she wrote: “For her faithful friend, I am most sorry – Billy Bellairs who looked after her so lovingly for years. She herself is in Caulfield hospital sick, run down and tired out & very bereft”.

During her years in Australia, Bellairs dedicated her time to volunteering at the Braille Library, translating English and French texts into Braille.66 Bellairs returned to England shortly afterwards, taking many of Cumbrae Stewart’s paintings with her. There, she renewed an old romance with a woman she met in Cassis. 67 Her family remember Bellairs as being a great story-teller, who was so proud of the four medals she was awarded for her service during the war, that she wore them regularly at Sunday dinners.

Cumbrae Stewart was dedicated to her art and maintained a consistent practice all her life. She was a quiet, elegant women, modest and accommodating. She was also a heavy smoker and although determined not to fall foul of the fate of most women of her day, her niece observed in 1932, that she made herself a slave to everyone. She was also prone to irrational fears. For instance, she was terrified of being buried alive and requested in her will that her wrists be slashed to ensure she was actually dead.

Cumbrae Stewart’s work is today held in the State collections of Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland, the National Gallery of Australia, and several regional galleries including the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery and Bendigo Art Gallery. It is also held in the Royal Collection in London and the Museo del Novecento in Milan. Despite this, much of her work has not been seen in the public domain for several decades. This is possibly as a result of the dark clouds that some contemporary critics have cast over her young nudes. Interest in her work has been somewhat renewed in recent years as a result of the industry’s drive to write female artists back in to the art-historic narrative. Most recently, several examples were included in Bayside Gallery’s Her Own Path exhibition in 200, in recognition of the early female artists of Bayside, and a pivotal major retrospective of her work was held at Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in 2003 under the curatorship of Rodney James.